Mardi Gras Exhibit

Since 1699, when Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville celebrated his arrival at the mouth of the Mississippi on Shrove Tuesday, Mardi Gras has been integrally linked to Louisiana's cultural heritage.

Hurricane Katrina Exhibit

Early in the morning on August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. When the storm made landfall, it had a Category 3 rating and brought sustained winds of 100–140 miles per hour stretching 400 miles across. The storm itself did a great deal of damage, but its aftermath was catastrophic. Levee breaches led to massive flooding, and many people charged that the federal government was slow to meet the needs of the people affected by the storm. Hundreds of thousands of people in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were displaced from their homes, and experts estimate that Katrina caused more than $100 billion in damage.New Orleans was at particular risk. Though about half the city actually lies above sea level, its average elevation is about six feet below sea level–and it is completely surrounded by water. Over the course of the 20th century, the Army Corps of Engineers had built a system of levees and seawalls to keep the city from flooding. The levees along the Mississippi River were strong and sturdy, but the ones built to hold back Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Borgne and the waterlogged swamps and marshes to the city’s east and west were much less reliable. Even before the storm, officials worried that those levees, jerry-built atop sandy, porous, erodible soil, might not withstand a massive storm surge. Neighborhoods that sat below sea level, many of which housed the city’s poorest and most vulnerable people, were at great risk of flooding.

By the time Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans early in the morning on Monday, August 29, it had already been raining heavily for hours. When the storm surge (as high as 9 meters in some places) arrived, it overwhelmed many of the city’s unstable levees and drainage canals. Water seeped through the soil underneath some levees and swept others away altogether. By 9 a.m., low-lying places like St. Bernard Parish and the Ninth Ward were under so much water that people had to scramble to attics and rooftops for safety. Eventually, nearly 80 percent of the city was under some quantity of water.

Many people acted heroically in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The Coast Guard, for instance, rescued some 34,000 people in New Orleans alone, and many ordinary citizens commandeered boats, offered food and shelter, and did whatever else they could to help their neighbors. Yet the government–particularly the federal government–seemed unprepared for the disaster. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) took days to establish operations in New Orleans, and even then did not seem to have a sound plan of action. Officials, even including President George W. Bush, seemed unaware of just how bad things were in New Orleans and elsewhere: how many people were stranded or missing; how many homes and businesses had been damaged; how much food, water and aid was needed. Katrina had left in her wake what one reporter called a “total disaster zone” where people were “getting absolutely desperate.”

Many had nowhere to go. At the Superdome in New Orleans, where supplies had been limited to begin with, officials accepted 15,000 more refugees from the storm on Monday before locking the doors. City leaders had no real plan for anyone else. Tens of thousands of people desperate for food, water and shelter broke into the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center complex, but they found nothing there but chaos. Meanwhile, it was nearly impossible to leave New Orleans: Poor people especially, without cars or anyplace else to go, were stuck. Some people tried to walk over the Crescent City Connector bridge to the nearby suburb of Gretna, but police officers with shotguns forced them to turn back. You can read about one account here.

In the aftermath of Katrina New Orleanians with their amazing resiliency and sense of humor made Mardi Gras costumes out of the blue tarps FEMA had provided.

Tommie Elton Mabry kept a Katrina diary on the walls of an apartment in the B.W. Cooper public housing development for eight weeks. Starting the day before the storm, Mabry chronicled the mundane doings of his daily life: a sore throat, the rain, a hangover, the loneliness, some pizza, a toothache. Though they were nothing more than a simple record of the experiences and emotions of one man, the entries taken together comprised a poignant and powerful testament to an epic event. They covered four walls, top to bottom.

Shortly before the Cooper development was torn down three years later, the Louisiana State Museum removed the paint from the walls, preserved it, and then installed it in the permanent Katrina exhibit.

Homeless on and off for much of his adult life, Mabry was eventually the sole occupant of the sprawling complex, staying on in defiance of the city’s evacuation order, dodging the housing authority and the New Orleans police – and coping with the 2 feet of water that covered the floors. On the sly, National Guardsmen patrolling the area looked after him, dropping off MREs (meals ready to eat) by the case and once delivering a steak for his dog, Red.

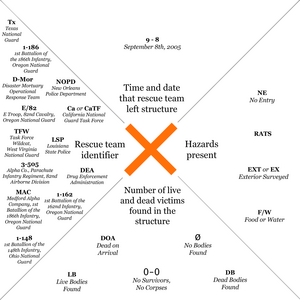

Instead of the International Search & Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG) marking system, in the United States, the FEMA marking system is used on searched structures as follows:

- A single diagonal slash indicates that a search in the building is in progress. This is used to indicate searcher locations and to avoid duplication of the search effort.

- An X inside a square means "Dangerous - Do Not Enter!"

- An X with writing around it means "Search Completed", with the time (and the date if appropriate) written above the X, the team conducting the search written to the left side of the X, the results of the search (number of victims removed, number of dead, type of search such as primary or secondary) written below the X, and any additional information noted about the structure to the right of the X.

- An X with writing around it means "Search Completed", with the time (and the date if appropriate) written above the X, the team conducting the search written to the left side of the X, the results of the search (number of victims removed, number of dead, type of search such as primary or secondary) written below the X, and any additional information noted about the structure to the right of the X.

United States FEMA marking (file photo)

According to the garage door exhibit below on September 2nd a member of either the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment or the 503rd Infantry Regiment searched the structure once attached to the door.

The horror stories of FEMA's failures were widespread in the aftermath of Katrina. A list of Hurricane Katrina and Fema Failures of FEMA Reported in Major Media can be found here. Some of the atrocities make you wonder if this was really the US government.

The menu items listed for these MRE costumes are a little difficult to read but they include such delectables as:

- 17th Street Canal Leek Soup

- Chalmette Fowl with Bush Lame Duck Sauce

- Artichoke FEMA

- FEMA Mumbo Gumbo

In true Louisiana style we were greeted by an impromptu brass band as we left the museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment